Peter Stumpp (died 1589) (whose name is also spelled as Peter Stube, Peter Stubbe, Peter Stübbe or Peter Stumpf) was a German farmer, accused of werewolfery, witchcraft and cannibalism. He was known as ‘the Werewolf of Bedburg’.

Sources

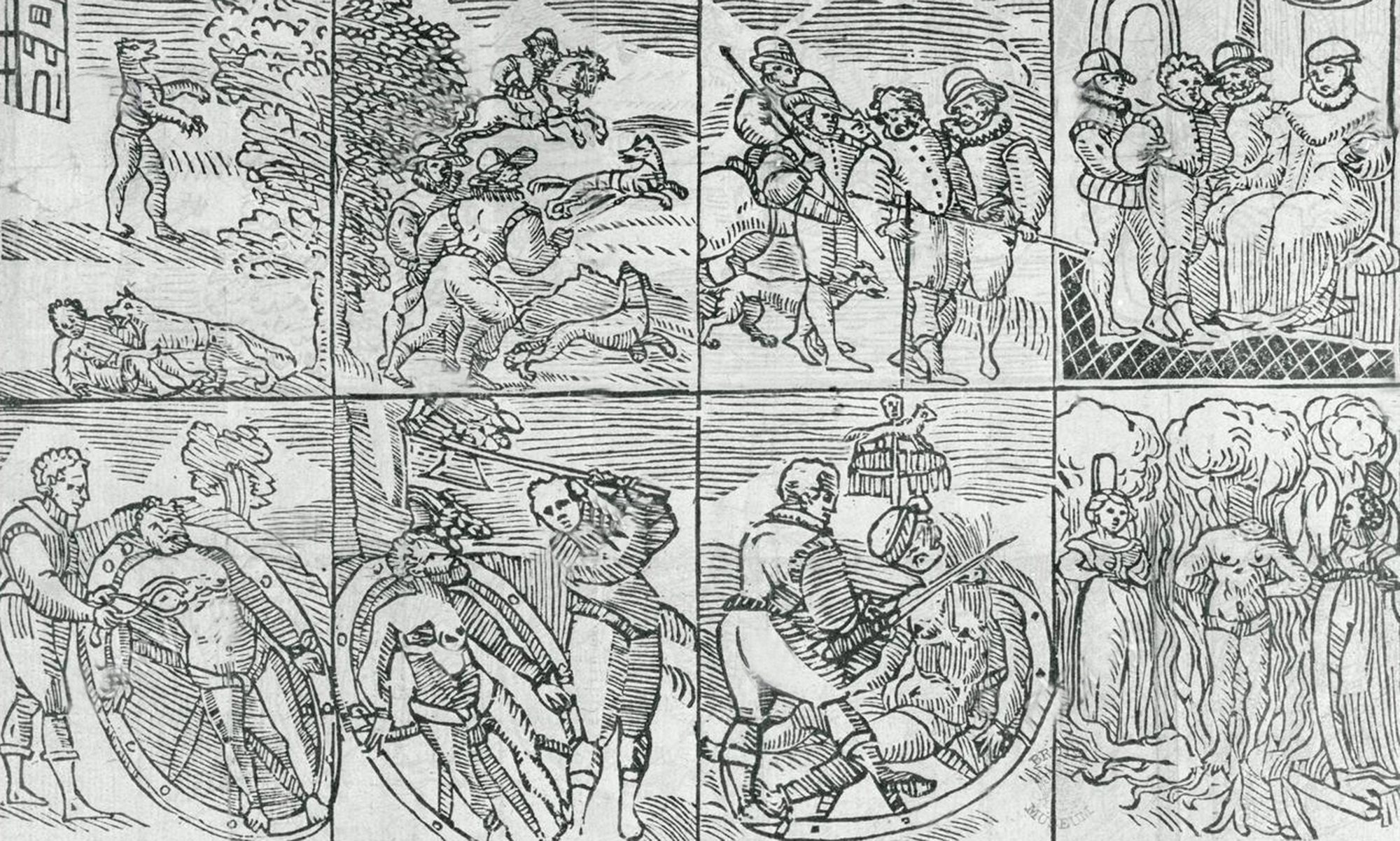

The most comprehensive source on the case is a pamphlet of 16 pages published in London in 1590, the translation of a German print of which no copies have survived. The English pamphlet, of which two copies exist (one in the British Museum and one in the Lambeth Library), was rediscovered by occultist Montague Summers in 1920. It describes Stumpp’s life, alleged crimes and the trial, and includes many statements from neighbours and witnesses of the crimes. Summers reprints the entire pamphlet, including a woodcut, on pages 253 to 259 of his work The Werewolf.

Additional information is provided by the diaries of Hermann von Weinsberg, a Cologne alderman, and by a number of illustrated broadsheets, which were printed in southern Germany and were probably based on the German version of the London pamphlet.The original documents seem to have been lost during the wars of the centuries that followed.

Contemporary reference was made to the pamphlet by Edward Fairfax in his firsthand account of the alleged witch persecution of his own daughters in 1621.

Biography

Peter Stumpp’s name is also spelled as Peter Stube, Peter Stub, Peter Stubbe, Peter Stübbe or Peter Stumpf, and other aliases include such names as Abal Griswold, Abil Griswold, and Ubel Griswold. The name “Stump” or “Stumpf” may have been given him as a reference to the fact that his left hand had been cut off leaving only a stump, in German “Stumpf”.[citation needed] It was alleged that as the “werewolf” had its left forepaw cut off, then the same injury proved the guilt of the man. Stumpp was born at the village of Epprath near the country-town of Bedburg in the Electorate of Cologne. His actual date of birth is not known, as the local church registers were destroyed during the Thirty Years’ War (1618–1648). He was a wealthy farmer of his rural community. During the 1580s, he seems to have been a widower with two children; a girl called Beele (Sybil), who seems to have been older than fifteen years old, and a son of an unknown age.

Accusations

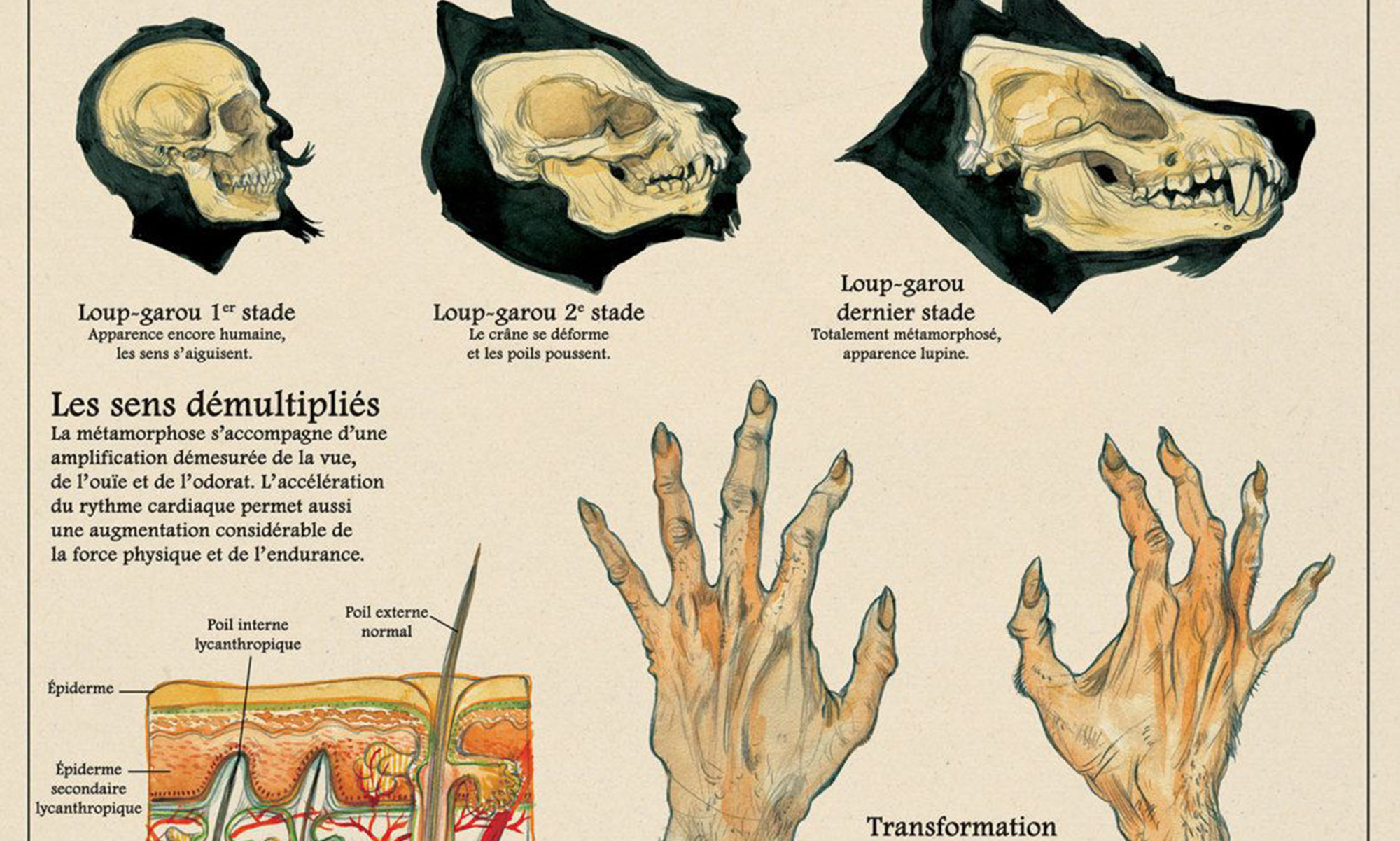

During 1589, Stumpp had one of the most lurid and famous werewolf trials of history. After being stretched on a rack, and before further torture commenced, he confessed to having practiced black magic since he was twelve years old. He claimed that the Devil had given him a magical belt or girdle, which enabled him to metamorphose into “the likeness of a greedy, devouring wolf, strong and mighty, with eyes great and large, which in the night sparkled like fire, a mouth great and wide, with most sharp and cruel teeth, a huge body, and mighty paws.” Removing the belt, he said, made him transform back to his human form. No such belt was ever found after his arrest.

For twenty-five years, Stumpp had allegedly been an “insatiable bloodsucker” who gorged on the flesh of goats, lambs, and sheep, as well as men, women, and children. Being threatened with torture he confessed to killing and eating fourteen children, two pregnant women, whose fetuses he ripped from their wombs and “ate their hearts panting hot and raw,” which he later described as “dainty morsels.” One of the fourteen children was his own son, whose brain he was reported to have devoured.

Not only was Stumpp accused of being a serial murderer and cannibal, but also of having an incestuous relationship with his daughter,[3] who was sentenced to die with him, and that he had coupled with a distant relative, which was also considered to be incestuous according to the law. In addition to this he confessed to having had intercourse with a succubus sent to him by the Devil.

Execution

The execution of Stumpp, on October 31, 1589, and of his daughter and mistress, is one of the most brutal on record: he was put to a wheel, where “flesh was torn from his body”, in ten places, with red-hot pincers, followed by his arms and legs. Then his limbs were broken with the blunt side of an axehead to prevent him from returning from the grave, before he was beheaded and his body burned on a pyre.His daughter and mistress had already been flayed, strangled and were burned along with Stumpp’s body. As a warning against similar behavior, local authorities erected a pole with the torture wheel and the figure of a wolf on it, and at the very top they placed Peter Stumpp’s severed head.

Background

There are a number of details of the text of the London pamphlet that are inconsistent with the historical facts.

The years during which Stumpp was supposed to have committed most of his crimes (1582–1589) were marked by internal warfare in the Electorate of Cologne after the abortive introduction of Protestantism by the former Archbishop Gebhard Truchsess von Waldburg. He had been assisted by Adolf, Count of Neuenahr, who was also the lord of Bedburg.

Stumpp was most certainly a convert to Protestantism. The war brought the invasion of armies of either side, the assaults by marauding soldiers and eventually an epidemic of the plague.

When the Protestants were defeated during 1587, Bedburg Castle became the headquarters of Catholic mercenaries commanded by the new lord of Bedburg—Werner, Count of Salm-Reifferscheidt-Dyck, who was a staunch Catholic determined to re-establish the Roman faith.

So it is not inconceivable that the werewolf trial was but a barely concealed political trial, with the help of which the new lord of Bedburg planned to bully the Protestants of the territory back into Catholicism. If it had been just another execution of an alleged werewolf and a couple of witches, as occurred about this time in various parts of Germany, the attendance of members of the aristocracy—perhaps including the new Archbishop and Elector of Cologne—would be surprising. Furthermore, the trial remained a singular event.

However, this does not mean that the charges were without basis in fact. The execution of a mere Protestant convert would have been deeply unlikely to have drawn the aristocratic attention Stumpp’s trial did, and while it was unlikely for the elite to attend to any given werewolf or witch trial, the sheer scale of Stumpp’s alleged crimes would have made it more visible to the public at large and the nobility.

In popular culture

English black metal band The Infernal Sea recorded a song called Skinwalker about the werewolf of Bedburg on their 2017 e.p Agents of Satan. The U.S. metal band Macabre recorded a song about Peter Stumpp, titled “The Werewolf of Bedburg”; it can be found on the Murder Metal album.

The German horror punk band The Other recorded a song about Peter Stumpp, titled “Werewolf of Bedburg”; it can be found on the Casket Case album.

In the Pine Deep Trilogy of novelist and folklorist Jonathan Maberry, Peter Stumpp is the supernatural villain Ubel Griswold. Since Griswold is actually one of Stumpp’s historical aliases, Maberry decided to use the name of Ubel Griswold instead of openly telling people that the villain was the infamous werewolf Peter Stumpp until later on in the third book of the series, Bad Moon Rising.

In the Jim Butcher book Fool Moon there are several characters that use enchanted wolf pelt belts to transform into a wolf form, similar to the belt Peter Stumpp claimed to have.

A reference to Peter Stumpp is also made in William Peter Blatty’s book, The Exorcist. When Father Karras and Kinderman talk about Satanism they say “Terrible, was this theory, Father, or fact?” “Well, there’s William Stumpf, for example. Or Peter. I can’t remember. Anyway, a German in the sixteenth century who thought he was a werewolf”.

The direct-to-video Big Top Scooby-Doo!, uses a portion of Lukas Mayer’s woodcut of the execution of Stumpp in 1589, though in the movie no mention of Stumpp is made. The portion used depicts a man cutting off a werewolf’s left paw (supposedly Stumpp in werewolf form) and a child being attacked by a werewolf. The woodcut scene shown in the film restores the werewolf’s left paw and removes the child in the second werewolf’s jaws, making it appear as if the swordsman is fighting one of the werewolves while another flees.

In the Doctor Who audio drama Loups-Garoux, Pieter Stubbe was in fact a werewolf. He managed to escape before he was executed and lived for another five centuries. He was defeated by the Fifth Doctor in Brazil in 2080. It is implied that he ate both the Grand Duchess Anastasia and Lord Lucan.

Journalist and fiction writer J.E. Reich partially based her short story “The Werewolves of Anspach,” on the life of Peter Stumpp.

The story of Peter Stumpp was also told in episode 3 of the podcast Lore, released on April 6, 2015. In 2017, the podcast episode was adapted into the fifth episode of the TV series adaptation of Lore, where he was played by Adam Goldberg.

The case inspired Neil MacKay’s novel, ‘The Wolf Trial’ (Glasgow: Freight Books, 2016. ISBN 978-1-910449-72-1)

Peter Stumpp is referenced in ‘The Werewolf of Bamburg’ by Oliver Potzsch. It briefly mentions his execution and crimes.

Peter Stumpp is referenced as a werewolf in “The Secret Life of Cooper Bennett” by Golden Czermak (ISBN 978-1976241550)